Ethical Decisions are Everywhere

The homeless guy I walked past. The hamburger I ate and the tip I left. The verbally abusive parent on the subway that I ignored. The $20 bill I found in the back of a cab. The elections.

Life, at work and at home, is full of ethical decisions, choices about how we ought to behave. Sometimes the answers are obvious. Often, the answers become less clear the more we think about them.

Are there moral facts or is ethics just about feelings? Are there objective and universal truths or are moral values merely social conventions? I think these are false choices: ethics can be at the same time facts and feelings, universal and local.

An Ethical Algorithm

But let’s think practically.

When I’m faced with a moral dilemma, and I have the luxury of time to think about it, I look at it from three perspectives. I give each a vote to avoid a tie: Aristotle, Kant and Mill. I also remember the empathetic wisdom of Rev. Stephanie Spellers.

Aristotle is associated with virtue ethics. We ought to build good habits of character so that following rules is natural. Wisdom, courage, temperance and justice are the four cardinal virtues. Would performing an act make me virtuous? In other words, would it make me a mensch (a person of integrity and honor)?

Aristotle is associated with virtue ethics. We ought to build good habits of character so that following rules is natural. Wisdom, courage, temperance and justice are the four cardinal virtues. Would performing an act make me virtuous? In other words, would it make me a mensch (a person of integrity and honor)?

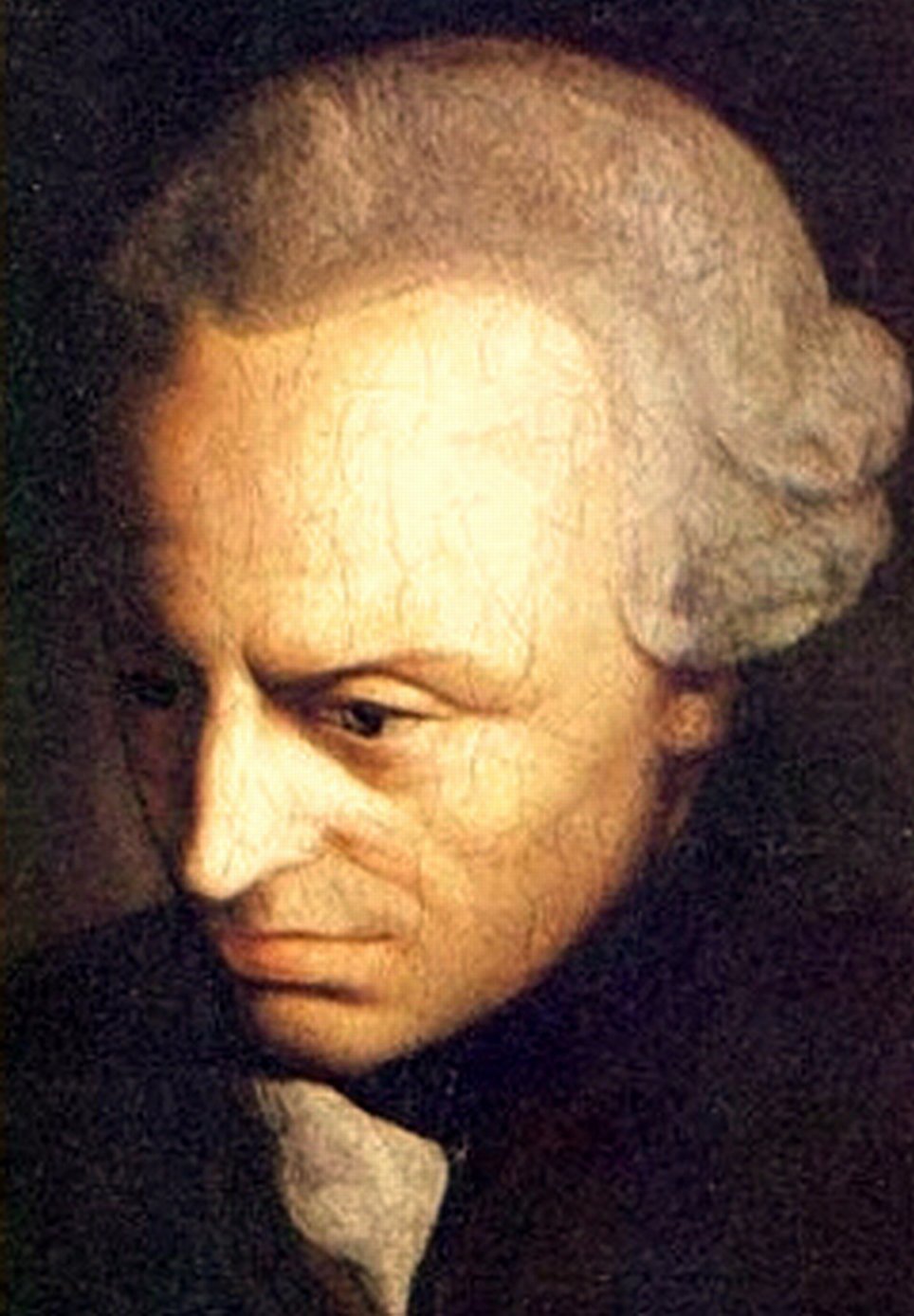

Then I “ask” Immanuel Kant. He’s associated with duty ethics. These are rules we must follow regardless of the consequences. For example, there is Kant’s categorical imperative that I must treat people as an end in themselves not as a means to an end. The ten commandments are another example. Will the act I’m considering be consistent with the rules?

Then I “ask” Immanuel Kant. He’s associated with duty ethics. These are rules we must follow regardless of the consequences. For example, there is Kant’s categorical imperative that I must treat people as an end in themselves not as a means to an end. The ten commandments are another example. Will the act I’m considering be consistent with the rules?

Third, I tap my inner John Stuart Mill, a leading proponent of utilitarianism. Will the act’s benefits exceed its costs? I try to limit the discount I apply to benefits/costs that occur far in the future or, if I’m being honest, people I care less about. So I ask whether the act increases my and the world’s welfare.

Third, I tap my inner John Stuart Mill, a leading proponent of utilitarianism. Will the act’s benefits exceed its costs? I try to limit the discount I apply to benefits/costs that occur far in the future or, if I’m being honest, people I care less about. So I ask whether the act increases my and the world’s welfare.

Being Bravely Ethical

But I’m not done yet. I know how subtle and automatic biases can be. So I also engage my empathy for others affected by my decision. I heard an amazing TEDx talk this past weekend by Stephanie Spellers, “How to Truly Listen”, which made me vow to “listen bravely” to people with whom I disagree.1 Then, if the majority of philosophers in my head vote for it, I go for it.

But I’m not done yet. I know how subtle and automatic biases can be. So I also engage my empathy for others affected by my decision. I heard an amazing TEDx talk this past weekend by Stephanie Spellers, “How to Truly Listen”, which made me vow to “listen bravely” to people with whom I disagree.1 Then, if the majority of philosophers in my head vote for it, I go for it.

Reasonable Short-Cuts

Of course, sometimes we don’t have time to make a thoughtful analysis. In these cases, I rely on heuristics, short-cuts like the golden rule or whether I’d be proud to have my act described on the front page of the New York Times or to my children.

That #$@&%*! Subway Panhandler

So here’s how the voting goes down for me and the panhandler I run into on the subway. Should I give them a buck?

- Aristotle: For. Giving a dollar is consistent with the virtue of justice and generosity.

- Kant: Against. Giving the dollar might assuage my guilt but it does nothing to materially improve their lives. It’s true that in their shoes, I’d want to get the dollar. But, I also think I might want incentive to find help at a charity. Also, it’s against MTA rules.

- Mill: Against. At first glance, the dollar has greater utility to the panhandler than to me, so giving it would increase overall social welfare. However, I am more confident that the dollar I give to a legitimate charity instead is more likely to go to its intended purpose.

- Spellers: I should talk to them. I should understand why they are asking for the money.1 By listening, I can empathize and make a more reasoned decision. This WNYC podcast was enlightening.

Normally, Against wins for me. So I give instead to effective charities like City Harvest. That said, I’m thinking I should take each case separately and engage more, when it’s safe to do so.2

It’s the Hard that Makes it Great

Ethical decision making is hard because reasonable, kind and thoughtful people can disagree. What’s crucial is that we are mindful of the little and big decisions we make and try to take different perspectives and have good reasons when making them.

*According to http://niram.org/read/.

117 year-old Jay Whysel offers a good heuristic: give only if they’re asking for food and not for money. Jay believes that a request for food is a reliable signal that the panhandler will use the donation legitimately.

Updated 3/2/18 with link to Tedx Video